library(haven)

library(tidyverse)

library(survey)Survey weighting

Introduction

Adjusting for Nonresponse

Propensity score weighting and stratification

Weighting: Creating tailored weights

In this exercise we are going to create tailored weights for a survey dataset. We will use the NHANES dataset, which is a survey dataset from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

This example is adapted from the course Creating Tailored Weights held by Understanding Society. You can find their implementation in Stata Here. Here we replicate this example in R.

The variables that define the sampling design characteristics are:

sampl: an ID variablestratid: a stratification variablelocation: a clustering variablefinalwgt: a design weight

The specific task is now, to create a tailored weight for the variable hdresult, which contains serum levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL). However, only 8708 out of 10,337 entries are valid. We will adjust for this missingness through a tailored weight. We assume that all people are eligible to have a valid value for hdresult and that those who don’t have the value are nonrespondents. To create these tailored weights, we will draw upon the base weight finalwgt and create a weight adjustment.

We will use the following packages

1. Loading the NHANES dataset

- First, load the NHANES dataset into R. The dataset is available through this link in the dta format and can be loaded using the

havenpackage. Then, familiarize yourself with the dataset.

# Load the NHANES II dataset

nhanes2 <- read_dta("https://www.stata-press.com/data/r16/nhanes2f.dta")2. Create a 0/1 indicator of response

To create a 0/1 indicator of response, where 0 is for nonrespondents and 1 is for respondents, use the hdresult variable. For simplicity treat missing values as non response.

# Create a 0/1 indicator of response

nhanes2 <- nhanes2 %>%

mutate(resp = ifelse(!is.na(hdresult), 1, 0))

# if hdresult is not missing, set resp to 1, otherwise 03. Predict the response using logistic regression

- Select suitable predictors for the logistic regression model. Ensure that the predictors do not have missing values. If they do, impute them with a simple procedure, such as taking their average category or mean.

# Display the summary of the predictors and check if they contain missing values

summary(nhanes2 %>% select(sex, race, age, weight,

bpsystol, region, health,

heartatk, diabetes, sizplace)) sex race age weight

Min. :1.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :20.00 Min. : 30.84

1st Qu.:1.000 1st Qu.:1.000 1st Qu.:31.00 1st Qu.: 60.67

Median :2.000 Median :1.000 Median :49.00 Median : 70.42

Mean :1.525 Mean :1.144 Mean :47.56 Mean : 71.90

3rd Qu.:2.000 3rd Qu.:1.000 3rd Qu.:63.00 3rd Qu.: 81.19

Max. :2.000 Max. :3.000 Max. :74.00 Max. :175.88

bpsystol region health heartatk

Min. : 65.0 Min. :1.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.00000

1st Qu.:114.0 1st Qu.:2.000 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:0.00000

Median :128.0 Median :3.000 Median :3.000 Median :0.00000

Mean :130.9 Mean :2.582 Mean :3.414 Mean :0.04577

3rd Qu.:142.0 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:0.00000

Max. :300.0 Max. :4.000 Max. :5.000 Max. :1.00000

NA's :2 NA's :2

diabetes sizplace

Min. :0.00000 Min. :1.000

1st Qu.:0.00000 1st Qu.:3.000

Median :0.00000 Median :5.000

Mean :0.04828 Mean :5.166

3rd Qu.:0.00000 3rd Qu.:8.000

Max. :1.00000 Max. :8.000

NA's :2 # Checking predictors and imputing missing values

nhanes2 <- nhanes2 %>%

mutate(

health = ifelse(is.na(health), 3, health), # impute missing values with 3

heartatk = ifelse(is.na(heartatk), 0, heartatk), # impute missing values with 0

diabetes = ifelse(is.na(diabetes), 0, diabetes) # impute missing values with 0

)

# Display the summary of the predictors again to confirm no missing values

summary(nhanes2 %>% select(sex, race, age, weight,

bpsystol, region, health,

heartatk, diabetes, sizplace)) sex race age weight

Min. :1.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :20.00 Min. : 30.84

1st Qu.:1.000 1st Qu.:1.000 1st Qu.:31.00 1st Qu.: 60.67

Median :2.000 Median :1.000 Median :49.00 Median : 70.42

Mean :1.525 Mean :1.144 Mean :47.56 Mean : 71.90

3rd Qu.:2.000 3rd Qu.:1.000 3rd Qu.:63.00 3rd Qu.: 81.19

Max. :2.000 Max. :3.000 Max. :74.00 Max. :175.88

bpsystol region health heartatk

Min. : 65.0 Min. :1.000 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.00000

1st Qu.:114.0 1st Qu.:2.000 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:0.00000

Median :128.0 Median :3.000 Median :3.000 Median :0.00000

Mean :130.9 Mean :2.582 Mean :3.414 Mean :0.04576

3rd Qu.:142.0 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:0.00000

Max. :300.0 Max. :4.000 Max. :5.000 Max. :1.00000

diabetes sizplace

Min. :0.00000 Min. :1.000

1st Qu.:0.00000 1st Qu.:3.000

Median :0.00000 Median :5.000

Mean :0.04827 Mean :5.166

3rd Qu.:0.00000 3rd Qu.:8.000

Max. :1.00000 Max. :8.000 - Using the variables you identified run a logistic regression model

# Logistic regression to predict response

model <- glm(resp ~ factor(sex) + factor(race) +

age + weight + factor(region) +

factor(diabetes) + factor(sizplace), # predictors

data = nhanes2, # dataset

family = binomial()) # binomial family for logistic regression

# Display the summary of the model

summary(model)

Call:

glm(formula = resp ~ factor(sex) + factor(race) + age + weight +

factor(region) + factor(diabetes) + factor(sizplace), family = binomial(),

data = nhanes2)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 3.038391 0.203450 14.934 < 2e-16 ***

factor(sex)2 0.133171 0.059871 2.224 0.026129 *

factor(race)2 0.233674 0.092552 2.525 0.011577 *

factor(race)3 -0.382336 0.183499 -2.084 0.037197 *

age -0.008039 0.001684 -4.774 1.81e-06 ***

weight -0.008089 0.001926 -4.201 2.66e-05 ***

factor(region)2 -0.200494 0.094796 -2.115 0.034428 *

factor(region)3 -0.928439 0.091653 -10.130 < 2e-16 ***

factor(region)4 -0.397968 0.093853 -4.240 2.23e-05 ***

factor(diabetes)1 -0.517688 0.113408 -4.565 5.00e-06 ***

factor(sizplace)2 -0.960051 0.113417 -8.465 < 2e-16 ***

factor(sizplace)3 -0.152250 0.120993 -1.258 0.208268

factor(sizplace)4 0.266558 0.139023 1.917 0.055192 .

factor(sizplace)5 0.454941 0.175049 2.599 0.009351 **

factor(sizplace)6 -0.385489 0.145213 -2.655 0.007939 **

factor(sizplace)7 0.693591 0.155897 4.449 8.63e-06 ***

factor(sizplace)8 0.379206 0.110780 3.423 0.000619 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 9006.6 on 10336 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 8425.9 on 10320 degrees of freedom

AIC: 8459.9

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5- Predict the response probabilities for the respondents

# Predict response probabilities for respondents

nhanes2 <- nhanes2 %>%

mutate(prob1 = ifelse(resp == 1,

predict(model, type = "response"), 0))

# predict response probability for respondents, set 0 for nonrespondents4. Create tailored weights

- Create a weight variable

cwgtthat is the inverse of the predicted response probability for respondents.

# Adjustment for the wave 1 base weight

nhanes2 <- nhanes2 %>%

mutate(cwgt = ifelse(prob1 != 0, 1/prob1, 0))

# if prob1 is not 0, set cwgt to 1/prob1, otherwise 0- Create the tailored weight

newweightby multiplying the base weightfinalwgtwith the weight adjustmentcwgt. Display the summary of the new weight.

# Create the tailored weight

nhanes2 <- nhanes2 %>%

mutate(newweight = finalwgt * cwgt)

# create the tailored weight by multiplying finalwgt with cwgt

# Display summary of the new weight

summary(nhanes2$newweight) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0 4437 9626 11303 15878 94397 5. Compare the old and new weights

- Create the survey design objects for the old and new weights.

# Old weight survey design

design_old <- svydesign(id = ~location,

strata = ~stratid,

weights = ~finalwgt,

data = nhanes2)

# New weight survey design

design_new <- svydesign(id = ~location,

strata = ~stratid,

weights = ~newweight,

data = nhanes2)- What are the mean estimates of

hdresultusing the old and new weights?

# Mean estimate of hdresult using old weight

mean_hdresult_old <- svymean(~hdresult, design = design_old, na.rm = TRUE)

# Mean estimate of hdresult using new weight

mean_hdresult_new <- svymean(~hdresult, design = design_new, na.rm = TRUE)Propensity score stratification

In this exercise you will analyse data from the data from the 2003 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) used to monitor health conditions in the US. A smaller version of the original dataset is available the PracTools package. It is named named nhis and it includes demographic variables only.

ID: Identification variablestratum: Sample design stratumpsu: Primary sampling unitsvywt: Survey weightsex: Gender (1 = male; 2 = female)age: Age (continuous)age_r: Recoded age (3 = 18-24 years; 4 = 25-44 years; 5 = 45-64 years; 6 = 65-69 years; 7 = 70-74 years; 8 = 75 years and older)hisp: Hispanic ethnicity (1 = Hispanic; 2 = Non-Hispanic)marital: Marital status (1 = Separated; 2 = Divorced; 3 = Married; 4 = Single/never married; 5 = Widowed; 9 = Unknown marital status)parents: Parent(s) of sample person present in the family (1 = Mother, no father; 2 = Father, no mother; 3 = Mother and father; 4 = Neither mother nor father)parents_r: Parent(s) of sample person present in the family recode (1 = Yes; 2 = No)educ: Education (1 = 8th grade or less; 2 = 9-12th grade, no high school diploma; 3 = High school graduate; 4 = General education development (GED) degree recipient; 5 = Some college, no degree; 6 = Associate’s degree, technical or vocational; 7 = Associate’s degree, academic program; 8 = Bachelor’s degree (BA, BS, AB, BBA); 9 = Master’s, professional, or doctoral degree)educ_r: Education recode (1 = High school, general education development degree (GED), or less; 2 = Some college; 3 = Bachelor’s or associate’s degree; 4 = Master’s degree & higher)race: Race (1 = White; 2 = Black; 3 = Other)resp: Respondent (0 = nonrespondent; 1 = respondent)

- Load the package using the following code

library(PracTools)

data("nhis")- Fit unweighted logistic, probit and c-log-log models to the

respvariable

- Use the covariates

age,sex,hispandrace

logit=glm (resp ~ age + as.factor(sex) + as.factor(hisp) + as.factor(race),

family=binomial(link = "logit"),

data=nhis)

probit=glm (resp ~ age + as.factor(sex) + as.factor(hisp) + as.factor(race),

family=binomial(link = "probit"),

data=nhis)

cloglog=glm (resp ~ age + as.factor(sex) + as.factor(hisp) + as.factor(race),

family=binomial(link = "cloglog"),

data=nhis)- Which variables are significant predictors in each of the models?

Look at the regression tables.

We can look at the following table:

| Dependent variable: | |||

| resp | |||

| logistic | probit | glm: binomial | |

| link = cloglog | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| age | -0.010*** | -0.006*** | -0.006*** |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| as.factor(sex)2 | -0.077 | -0.046 | -0.044 |

| (0.070) | (0.042) | (0.041) | |

| as.factor(hisp)2 | 0.405*** | 0.246*** | 0.241*** |

| (0.088) | (0.054) | (0.054) | |

| as.factor(race)2 | -0.212** | -0.128** | -0.124** |

| (0.098) | (0.060) | (0.059) | |

| as.factor(race)3 | -0.352** | -0.216** | -0.220** |

| (0.160) | (0.098) | (0.100) | |

| Constant | 1.015*** | 0.622*** | 0.272*** |

| (0.114) | (0.069) | (0.068) | |

| Observations | 3,911 | 3,911 | 3,911 |

| Log Likelihood | -2,400.759 | -2,400.822 | -2,400.990 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 4,813.519 | 4,813.644 | 4,813.980 |

| Note: | p<0.1; p<0.05; p<0.01 | ||

All variables (including the intercept) are significant in all models, except for sex.

- Compare the predicted probabilities from the three models. You can make a table or a plot. Predicted probabilities are in

$fitted.values

library(kableExtra)

pred.logit=logit$fitted.values

pred.probit=probit$fitted.values

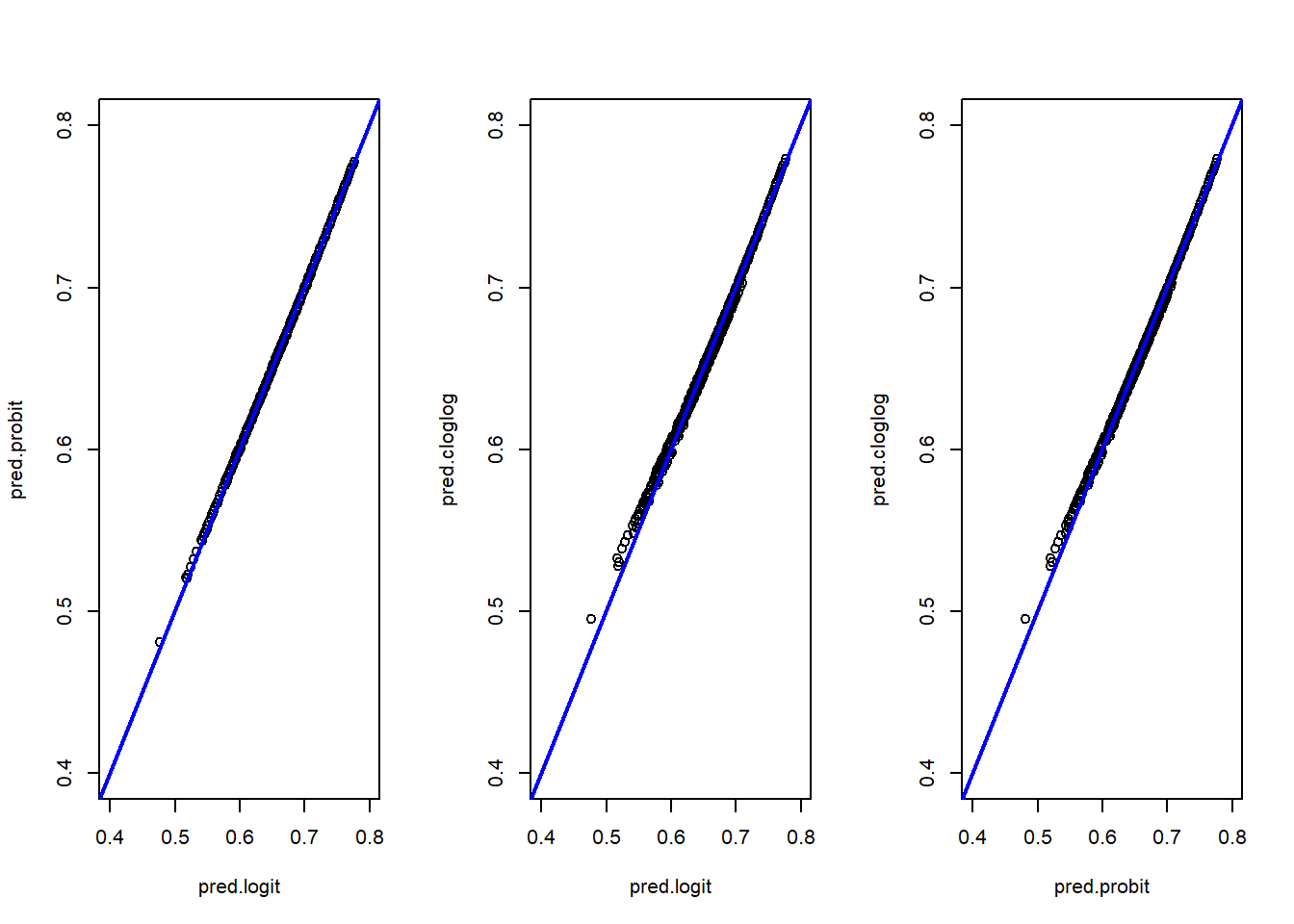

pred.cloglog=cloglog$fitted.valuesWe can compare each predicted probabilities against the other:

#This is in base R but you can use ggplot2

par(mfrow = c(1, 3))

plot(pred.logit,pred.probit,xlim=c(0.4,0.8),ylim=c(0.4,0.8))

abline(0,1, col="blue",lwd=2)

plot(pred.logit,pred.cloglog,xlim=c(0.4,0.8),ylim=c(0.4,0.8))

abline(0,1, col="blue",lwd=2)

plot(pred.probit,pred.cloglog,xlim=c(0.4,0.8),ylim=c(0.4,0.8))

abline(0,1, col="blue",lwd=2)

We can make a summary table:

summary(pred.logit) %>%

bind_rows(summary(pred.probit)) %>%

bind_rows(summary(pred.cloglog)) %>%

add_column(model=c("logit","probit","cloglog"),.before=1) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(latex_options = "HOLD_position")| model | Min. | 1st Qu. | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logit | 0.4769137 | 0.6585878 | 0.6924415 | 0.6901048 | 0.7260404 | 0.7765047 |

| probit | 0.4808753 | 0.6584612 | 0.6919716 | 0.6900877 | 0.7258562 | 0.7773489 |

| cloglog | 0.4951173 | 0.6585117 | 0.6917511 | 0.6900942 | 0.7255815 | 0.7791557 |

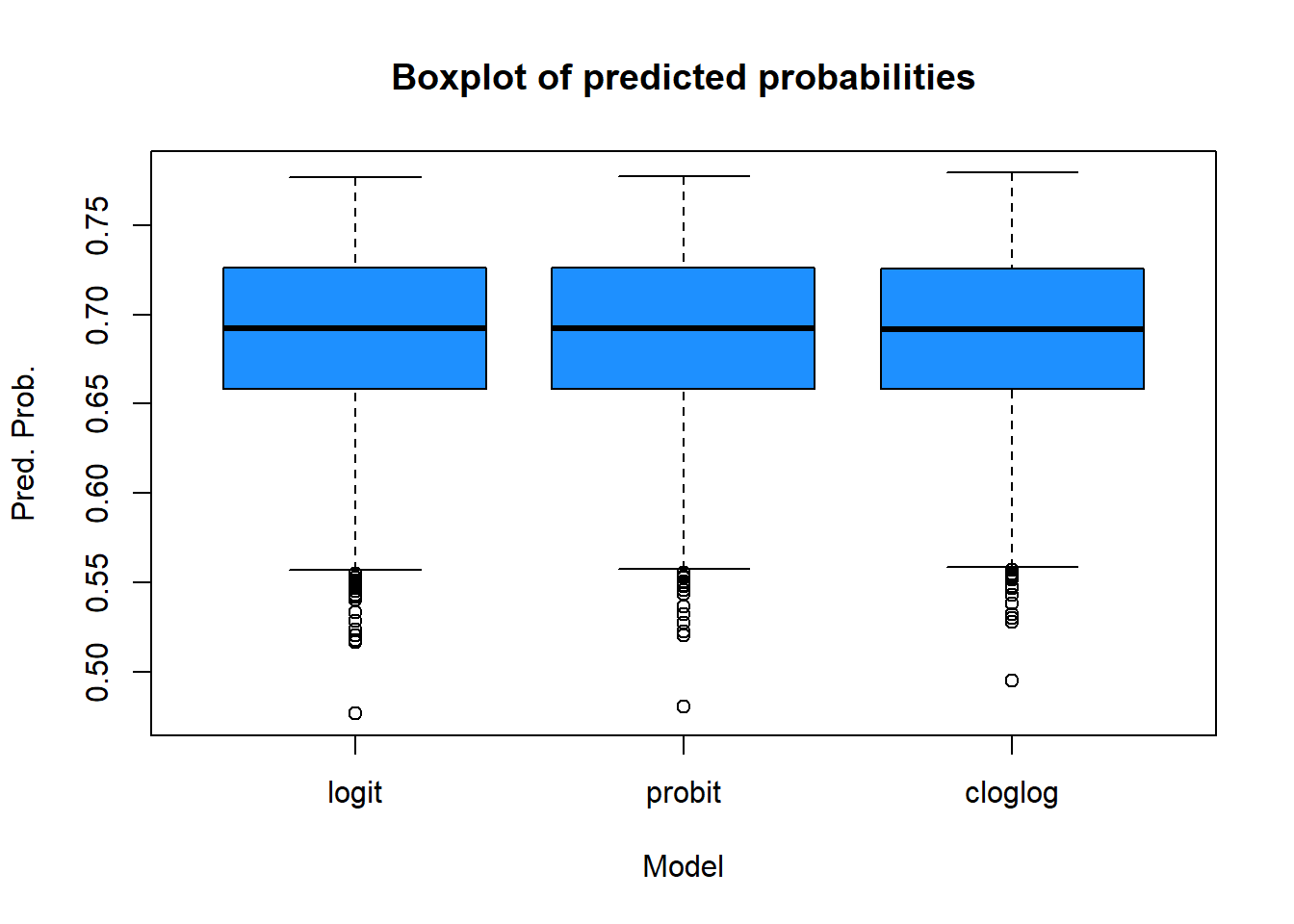

And some boxplots:

boxplot(pred.logit,pred.probit,pred.cloglog,

main="Boxplot of predicted probabilities",

xlab="Model",

ylab="Pred. Prob.",

col="dodgerblue",

border="black")

axis(1,at=c(1,2,3),labels=c("logit","probit","cloglog"))

The three models produce very similar results. The logit and probit models are almost identical, while the cloglog model shows slight differences, particularly at the extreme low end of the predicted probabilities (as seen in the scatter plots and box plots). Analyzing the min-max values and quartiles leads to the same conclusion: the models are closely aligned overall.

- Use the predicted response probabilities from the logistic regression that used all covariates and create two versions of propensity classes:

- Five classes with an equal number of respondents plus nonrespondents in each. Use

pclassin order to make classes.

p.class5 <- pclass(formula=resp ~ age + as.factor(sex) + as.factor(hisp) + as.factor(race),

type="unwtd",data=nhis,link="logit", numcl=5)- Ten classes. Report the breaks used for the five and ten classes and the number of cases assigned to each class. (Check to see that all cases were assigned a non-missing class value. Use the parameter `useNA=“always”` in table in order to see whether NAs were created.)

p.class10 <- pclass(formula=resp ~ age + as.factor(sex) + as.factor(hisp) + as.factor(race),

type="unwtd",data=nhis,link="logit", numcl=10)- How do the five and ten classes compare to each other?

table(p.class5$p.class,useNA="always") %>%

kable(col.names = c("Boundaries","Count of persons")) %>%

kable_styling(latex_options = "HOLD_position")| Boundaries | Count of persons |

|---|---|

| [0.477,0.651] | 783 |

| (0.651,0.68] | 782 |

| (0.68,0.706] | 782 |

| (0.706,0.734] | 782 |

| (0.734,0.777] | 782 |

| NA | 0 |

table(p.class10$p.class,useNA="always") %>%

kable(col.names = c("Boundaries","Count of persons")) %>%

kable_styling(latex_options = "HOLD_position")| Boundaries | Count of persons |

|---|---|

| [0.477,0.629] | 392 |

| (0.629,0.651] | 391 |

| (0.651,0.665] | 391 |

| (0.665,0.68] | 391 |

| (0.68,0.692] | 391 |

| (0.692,0.706] | 391 |

| (0.706,0.72] | 391 |

| (0.72,0.734] | 391 |

| (0.734,0.75] | 391 |

| (0.75,0.777] | 391 |

| NA | 0 |

All cases have been assigned a non-missing class value, and the number of individuals is nearly as expected. The 10 classes also show greater homogeneity.

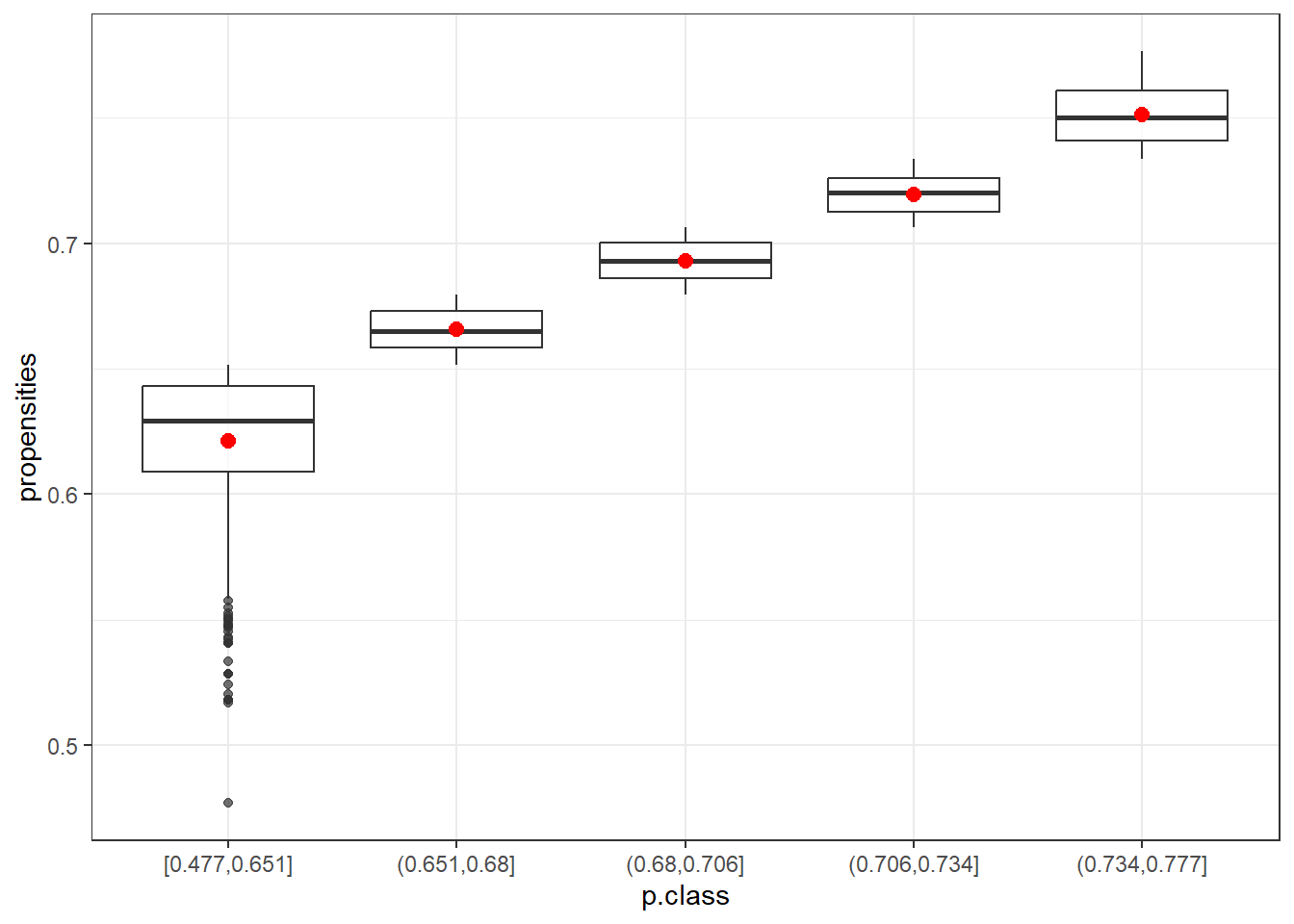

- How do the class adjustments compare to using the inverses of individual propensity estimates as adjustments?

data5=data.frame(p.class5)

ggplot(data5, aes(x=p.class, y=propensities)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha=0.7) +

stat_summary(fun.y=mean, geom="point", shape=20, size=4, color="red", fill="red") +

theme(legend.position="none") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette="Set1")+theme_bw()Warning: The `fun.y` argument of `stat_summary()` is deprecated as of ggplot2 3.3.0.

ℹ Please use the `fun` argument instead.

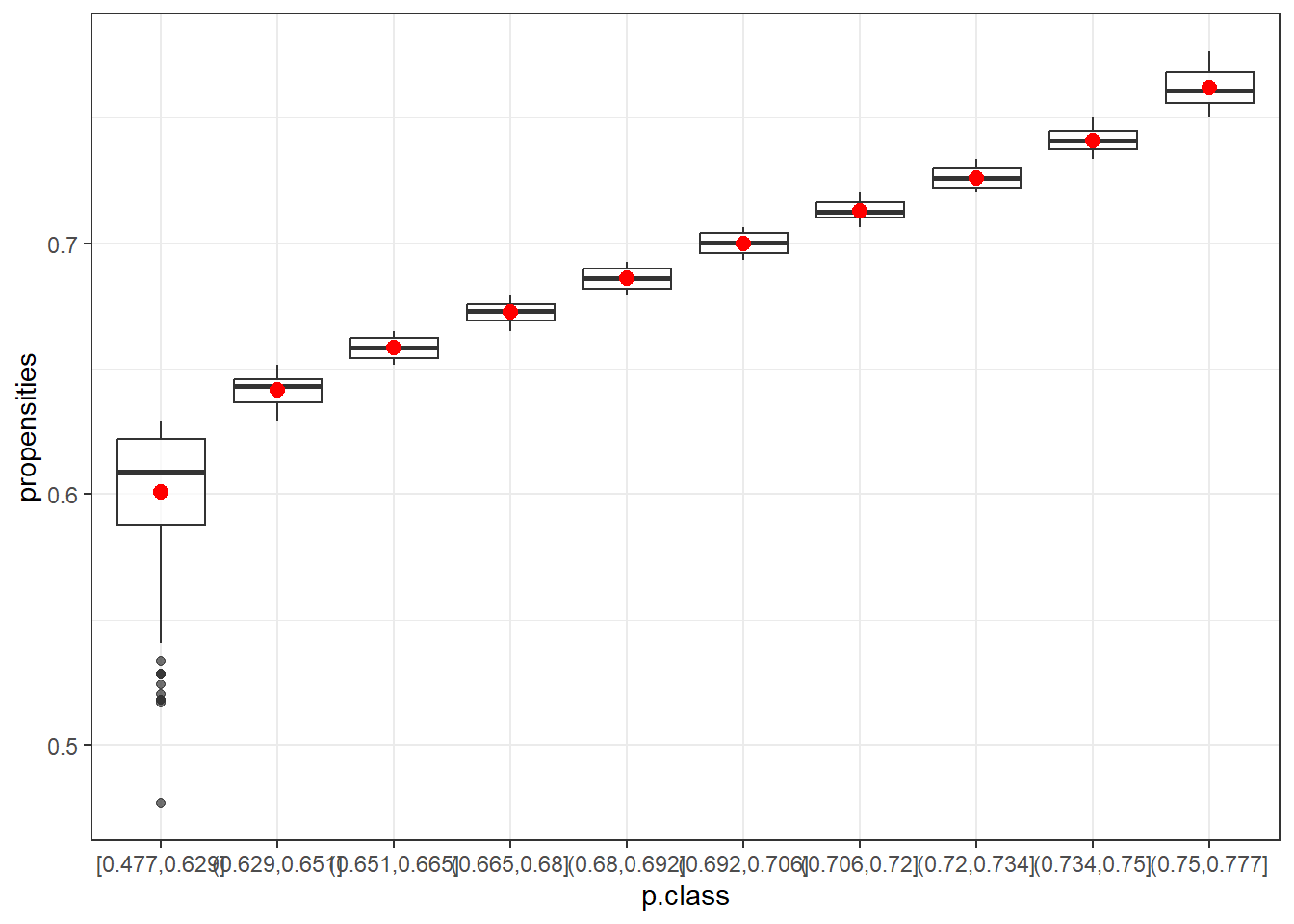

data10=data.frame(p.class10)

ggplot(data10, aes(x=p.class, y=propensities)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha=0.7) +

stat_summary(fun.y=mean, geom="point", shape=20, size=4, color="red", fill="red") +

theme(legend.position="none") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette="Set1")+theme_bw()

The box plots show that the first class (in both cases) is the most variable. After that, the range of propensities decreases. Using the mean (red) or the median helps to smooth out more extreme adjustments, which is especially beneficial for the first class. This highlights the advantage of using classes instead of raw propensity values.

- Which set of adjustment values would you recommend and why?

Think about it and discuss it in groups.

Extra exercises

If the ranges of estimated propensities in each class is small, you can use a single propensity value for each class. There are several options:

Calculate the five alternative values of NR weight adjustment shown in the box below.

For the weighted adjustments, use the svywt variable. Discuss how the five alternative values of adjustments compare within the two models with five and ten classes compare to each other

Unweighted average: \(\hat{\phi}_c = \frac{1}{n_c} \sum_{i \in s_c} \hat{\phi}(x_i)\) where \(n_c\) is the unweighted number of cases in class c

Weighted average: \(\hat{\phi}_c = \frac{\sum_{i \in s_c}d_i\hat{\phi}(x_i)}{\sum_{i \in s_c}d_i}\) where \(d_i\) is the base weight and the sum of \(d_i\) is the estimated number of population units in class \(c\)

Unweighted response rate: \(\hat{\phi}_c = n_{cR}/n_c\) where \(n_{cR}\) is the unweighted number of respondents in class c

Weighted response rate: \(\sum_{i \in s_{cR}}d_i/\sum_{i \in s_c}d_i\) where \(n_c\) is the unweighted number of cases in class c

Unweighted median: \(\hat{\phi}_c = median [\hat{\phi}(x_i)]_{i \in s_c}\) where \(n_c\) is the unweighted number of cases in class c

We compute the results for the case with 5 an 10 class respectively.

unw5=by(data=p.class5$propensities, p.class5$p.class, mean)

weigh5=by(data=data.frame(preds=p.class5$propensities, wt=nhis[,"svywt"]),

p.class5$p.class, function(x) {weighted.mean(x$preds,x$wt)})

unw.resp5=by(as.numeric(nhis[,"resp"]), p.class5$p.class, mean)

weigh.resp5=by(data=data.frame(resp=as.numeric(nhis[,"resp"]),wt=nhis[,"svywt"]),

p.class5$p.class, function(x) {weighted.mean(x$resp,x$wt)})

med5=by(p.class5$propensities, p.class5$p.class, median)unw10=by(data=p.class10$propensities, p.class10$p.class, mean)

weigh10=by(data=data.frame(preds=p.class10$propensities, wt=nhis[,"svywt"]),

p.class10$p.class, function(x) {weighted.mean(x$preds,x$wt)})

unw.resp10=by(as.numeric(nhis[,"resp"]), p.class10$p.class, mean)

weigh.resp10=by(data=data.frame(resp=as.numeric(nhis[,"resp"]),wt=nhis[,"svywt"]),

p.class10$p.class, function(x) {weighted.mean(x$resp,x$wt)})

med10=by(p.class10$propensities, p.class10$p.class, median)Then, we compare the results considering the following tables:

| Count of persons | Unw. avg. prop. | W. avg. prop. | Unw. RR | W. RR | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.477,0.651] | 783 | 0.6211 | 0.6237 | 0.6271 | 0.6463 | 0.6294 |

| (0.651,0.68] | 782 | 0.6656 | 0.6656 | 0.6662 | 0.6677 | 0.6651 |

| (0.68,0.706] | 782 | 0.6930 | 0.6933 | 0.6739 | 0.6859 | 0.6929 |

| (0.706,0.734] | 782 | 0.7195 | 0.7196 | 0.7353 | 0.7338 | 0.7201 |

| (0.734,0.777] | 782 | 0.7514 | 0.7521 | 0.7481 | 0.7623 | 0.7503 |

| Count of persons | Unw. avg. prop. | W. avg. prop. | Unw. RR | W. RR | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.477,0.629] | 392 | 0.6008 | 0.6026 | 0.5765 | 0.5915 | 0.6090 |

| (0.629,0.651] | 391 | 0.6415 | 0.6416 | 0.6777 | 0.6930 | 0.6430 |

| (0.651,0.665] | 391 | 0.6586 | 0.6585 | 0.6547 | 0.6577 | 0.6586 |

| (0.665,0.68] | 391 | 0.6727 | 0.6727 | 0.6803 | 0.6820 | 0.6731 |

| (0.68,0.692] | 391 | 0.6861 | 0.6862 | 0.6803 | 0.6833 | 0.6860 |

| (0.692,0.706] | 391 | 0.6999 | 0.7000 | 0.6650 | 0.6857 | 0.7002 |

| (0.706,0.72] | 391 | 0.7131 | 0.7131 | 0.7161 | 0.7092 | 0.7126 |

| (0.72,0.734] | 391 | 0.7259 | 0.7260 | 0.7545 | 0.7562 | 0.7260 |

| (0.734,0.75] | 391 | 0.7408 | 0.7407 | 0.7596 | 0.7710 | 0.7411 |

| (0.75,0.777] | 391 | 0.7619 | 0.7622 | 0.7366 | 0.7551 | 0.7610 |

Overall, for both 5 and 10 classes, we observe that values generally increase across classes, with all five methods producing similar results. The first and last classes show a wider range of values.

When comparing the results between 5 and 10 classes, the range is narrower in the 10-class scenario. While using more classes can help reduce bias due to nonresponse, it may also lead to higher variances. Typically, 5 classes are recommended when the sample size is not large. In this case, opting for 5 classes seems appropriate.

- Check covariate balance according to D’Agostino method. Is balancing achieved? Discuss it.

The idea is simple: after classes are formed, you check if there is a difference in the covariate means. The covariate means should be different between classes but within a class the means of the covariates should be the same for respondents and nonrespondents. This is consistent with the idea that the response propensity is the same for all units withing a class.

To check balance on covariates you need to:

for quantitative x’s: fit an ANOVA model, where

x = p.class + resp + p.class*respfor dichtonomous x’s: fit a logistic model, where

logit(x) = p.class + resp + p.class*resp

The coefficients on resp and the interaction p.class*respshoud be nonsignificant.

The coefficients on p.classshould be nonzero and different from each other

In addition you can also look at the covariate means table using p.class*resp

This is an example, you can proceed with all the covariates

p.class <- p.class5$p.class

#standard check

chk1 <- glm(age ~ p.class + resp + p.class*resp, data = nhis)

# An additional step is to fit a second model that only inlcudes p.class

# and test wether chk1 and chk2 are equivalent

chk2 <- glm(age ~ p.class, data = nhis)

summary(chk1)

Call:

glm(formula = age ~ p.class + resp + p.class * resp, data = nhis)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 60.5000 0.8266 73.189 < 2e-16 ***

p.class(0.651,0.68] -8.5230 1.2032 -7.083 1.66e-12 ***

p.class(0.68,0.706] -15.9314 1.2107 -13.159 < 2e-16 ***

p.class(0.706,0.734] -19.7995 1.2834 -15.427 < 2e-16 ***

p.class(0.734,0.777] -32.4594 1.3024 -24.923 < 2e-16 ***

resp -1.6242 1.0439 -1.556 0.1198

p.class(0.651,0.68]:resp -1.1512 1.4957 -0.770 0.4415

p.class(0.68,0.706]:resp 3.6021 1.5003 2.401 0.0164 *

p.class(0.706,0.734]:resp 2.5098 1.5494 1.620 0.1053

p.class(0.734,0.777]:resp 2.3272 1.5632 1.489 0.1366

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for gaussian family taken to be 199.5277)

Null deviance: 1188013 on 3910 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 778357 on 3901 degrees of freedom

AIC: 31823

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 2summary(chk2)

Call:

glm(formula = age ~ p.class, data = nhis)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 59.4815 0.5053 117.70 <2e-16 ***

p.class(0.651,0.68] -9.3536 0.7149 -13.08 <2e-16 ***

p.class(0.68,0.706] -13.5799 0.7149 -19.00 <2e-16 ***

p.class(0.706,0.734] -18.1298 0.7149 -25.36 <2e-16 ***

p.class(0.734,0.777] -30.9150 0.7149 -43.24 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for gaussian family taken to be 199.9602)

Null deviance: 1188013 on 3910 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 781044 on 3906 degrees of freedom

AIC: 31827

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 2anova(chk2, chk1, test="Chisq")Analysis of Deviance Table

Model 1: age ~ p.class

Model 2: age ~ p.class + resp + p.class * resp

Resid. Df Resid. Dev Df Deviance Pr(>Chi)

1 3906 781044

2 3901 778357 5 2687 0.01937 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1#p-val non significant: balance is fine

#For hispanic you need to recode the data.

new.hisp <- abs(nhis$hisp-2)

#standard check

chk1 <- glm(new.hisp ~ p.class + resp + p.class*resp, family=binomial(link = "logit"), data = nhis)When running a model to check balance on covariates, you might encounter anomalous results, such as extremely large estimates of standard errors. This could indicate “quasi-complete” separation in the dataset, where one or more observations have a predicted probability very close to 1. In such cases, a parameter estimate may diverge to infinity.

While this poses a significant problem if your goal is to identify covariates associated with the occurrence of a particular characteristic, it does not affect the formation of propensity classes when checking covariate balance.

Adjusting for Nonresponse and Coverage

In this exercise we use a larger version of the NHIS dataset that we used in the previous exercise. This dataset, named nhis.large, also contain some health-related variables. We want to estimate the number of persons covered by Medicaid, a type of US governamental assistance for medical care provided to the poor.

We treat the large sample as reference population data. To the purpose of our exercise we also consider a probability sample which is extracted from the NHIS dataset but introducing coverage errors.

Your objective is to perform different adjustment methods, namely, poststratification, raking and GREG calibration.

- Load the data

Load the nhis.large dataset and recode hisp into three categories (collapse category 4 and 3).

data("nhis.large")

nhis.large1 <- nhis.large %>%

mutate(hisp.r = ifelse(hisp==4,3,hisp))

load("samdat.rda")Define the sampling design of the sample

This time specify the weights (N/n) and the finite population correction equal to the sampling fraction (n/N)

N <- nrow(nhis.large1)

n <-nrow(samdat)

d <- rep(N/n, n)

f1 <- rep(n/N, n)

nhis.dsgn <- svydesign(ids = ~0, # no clusters

strata = NULL, # no strata

fpc = ~f1,

data = data.frame(samdat),

weights = ~d)Poststratification

- Compute the population total in the poststrata defined by

age.grpandhisp.r

N.PS <- xtabs(~ age.grp + hisp.r, data = nhis.large1)- Implement

postStratifyspecifyingage.grp + hisp.rin the strata argument.

ps.dsgn <- postStratify(design = nhis.dsgn,

strata = ~age.grp + hisp.r,

population = N.PS)Raking

Compute the population total for the variable

age.grpandhisp.rGive appropriate names that match variable names in the raking and GREG models.

N.age <- table(nhis.large1[, "age.grp"])

N.hisp <- table(nhis.large1[, "hisp.r"])

pop.totals <- c('(Intercept)' = N, N.age[-1], N.hisp[-1])

names(pop.totals)=c("(Intercept)","as.factor(age.grp)2",

"as.factor(age.grp)3", "as.factor(age.grp)4",

"as.factor(age.grp)5" ,"as.factor(hisp.r)2",

"as.factor(hisp.r)3")- Implement raking specifying

~ as.factor(age.grp) + as.factor(hisp.r)in theformulaargument.

rake.dsgn <- calibrate(design = nhis.dsgn,

formula = ~ as.factor(age.grp) + as.factor(hisp.r),

calfun = "raking",

population = pop.totals)Verify that weights are calibrated for x’s

Compare the total for

age.grpandhisp.rcomputed usingrake.dsgnwith the population totalspop.totals

svytotal(~as.factor(age.grp), rake.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(age.grp)1 5991 0

as.factor(age.grp)2 2014 0

as.factor(age.grp)3 6124 0

as.factor(age.grp)4 5011 0

as.factor(age.grp)5 2448 0svytotal(~as.factor(hisp.r), rake.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(hisp.r)1 5031 0

as.factor(hisp.r)2 12637 0

as.factor(hisp.r)3 3920 0pop.totals (Intercept) as.factor(age.grp)2 as.factor(age.grp)3 as.factor(age.grp)4

21588 2014 6124 5011

as.factor(age.grp)5 as.factor(hisp.r)2 as.factor(hisp.r)3

2448 12637 3920 GREG

- Implement GREG calibration specifying

~ as.factor(age.grp) + as.factor(hisp.r)in theformulaargument.

greg.dsgn <- calibrate(design = nhis.dsgn,

formula = ~ as.factor(age.grp) + as.factor(hisp.r),

calfun = "linear",

population = pop.totals)Verify that weights are calibrated for x’s

Compare the total for

age.grpandhisp.rcomputed usinggreg.dsgnwith the population totalspop.totals

svytotal(~as.factor(age.grp), greg.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(age.grp)1 5991 0

as.factor(age.grp)2 2014 0

as.factor(age.grp)3 6124 0

as.factor(age.grp)4 5011 0

as.factor(age.grp)5 2448 0svytotal(~as.factor(hisp.r), greg.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(hisp.r)1 5031 0

as.factor(hisp.r)2 12637 0

as.factor(hisp.r)3 3920 0pop.totals (Intercept) as.factor(age.grp)2 as.factor(age.grp)3 as.factor(age.grp)4

21588 2014 6124 5011

as.factor(age.grp)5 as.factor(hisp.r)2 as.factor(hisp.r)3

2448 12637 3920 Compare the three methods

Compute the total and the proportion of individuals covered by Medicaid (1=yes, 2=no) using:

the original sampling weights

the poststratification weights

the raking weights

the GREG weights

svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), nhis.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 1823.8 250.18

as.factor(medicaid)2 17190.2 272.46svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), ps.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2492.1 317.07

as.factor(medicaid)2 18638.1 334.06svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), rake.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2555.9 330.66

as.factor(medicaid)2 18516.9 351.43svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), greg.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2534.3 327.89

as.factor(medicaid)2 18539.7 349.04svyciprop(~as.factor(medicaid)==1, nhis.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) 2.5% 97.5%

as.factor(medicaid) == 1 0.0959 0.0730 0.1250svyciprop(~as.factor(medicaid)==1, ps.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) 2.5% 97.5%

as.factor(medicaid) == 1 0.1179 0.0916 0.1506svyciprop(~as.factor(medicaid)==1, rake.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) 2.5% 97.5%

as.factor(medicaid) == 1 0.1213 0.0938 0.1555svyciprop(~as.factor(medicaid)==1, greg.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) 2.5% 97.5%

as.factor(medicaid) == 1 0.120 0.093 0.154#true

prop.table(table(nhis.large1[, "medicaid"]))

1 2

0.1071194 0.8928806 The results are quite similar.

Extra exercises

Note that applying poststratification with a single variable is equivalent to apply GREG.

Apply poststratification and then GREG considering only

age.grp.Remember to define population total (and names) again.

N.PS1 <- xtabs(~ age.grp, data = nhis.large1)

N <- nrow(nhis.large1)

N.age <- table(nhis.large1[, "age.grp"])

pop.totals1 <- c('(Intercept)' = N, N.age[-1])

names(pop.totals1)=c("(Intercept)","as.factor(age.grp)2",

"as.factor(age.grp)3",

"as.factor(age.grp)4",

"as.factor(age.grp)5")

ps.dsgn1 <- postStratify(design = nhis.dsgn,

strata = ~age.grp,

population = N.PS1)

greg.dsgn1 <- calibrate(design = nhis.dsgn,

formula = ~ as.factor(age.grp),

calfun = "linear",

population = pop.totals1)

svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), ps.dsgn1, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2211.4 292.27

as.factor(medicaid)2 18919.9 315.91svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), greg.dsgn1, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2211.4 292.27

as.factor(medicaid)2 18919.9 315.91- Continue the GREG exercise and trim your weights to be between 30 and 65

greg.trim <- trimWeights(design = greg.dsgn,

lower = 30,

upper = 65,

strict = TRUE)

svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), greg.dsgn, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2534.3 327.89

as.factor(medicaid)2 18539.7 349.04svytotal(~as.factor(medicaid), greg.trim, na.rm=TRUE) total SE

as.factor(medicaid)1 2502.3 323.26

as.factor(medicaid)2 18569.2 345.89- Repeat the GREG calibration specifying that the final weights should be between 0.5 and 1.5 times the original weights. Does the calibration work or fail?

Hint: Use bounds = c(0.5,1.5)

greg.bound <- calibrate(design = nhis.dsgn,

formula = ~ as.factor(age.grp) + as.factor(hisp.r),

calfun = "linear",

population = pop.totals,

bounds = c(0.5,1.5))The calibration algorithm fails.

Acknowledgments

Some of the exercises are adapted from:

Valliant, R., Dever, J. A., & Kreuter, F. (2018). Practical tools for designing and weighting survey samples (Vol. 1). New York: Springer.

Creating Tailored Weights - by Understanding Society